Back to Basics

This article is going to break down a hedged physical metals trade in its simplest form for a contract pricing on a single cash settlement date on the LME. I often find that newcomers to the industry get bogged down in terminology and more advanced concepts that they forget to master the basic principles of hedging.

First we will walk through the trade using round numbers to introduce the concept of equal and opposite. Then we will introduce some basis risk to the equation. We will then finish with a real-life trade example that generates profits for a trader.

This will be a very plain vanilla example, and there are of course many nuances to different metals, exchanges, and settlement styles, prompt dates, forward curves, and many other important factors to risk management. But provided you can understand the basic structure of a physical deal where price risk is being mitigated, you will be well on your way to understanding how companies protect their margins.

For a physical trader to mitigate the price risk of the underlying commodity, they can enter into futures trades - provided of course there is enough liquidity to execute the required volume, and that futures exchange is highly correlated to the physical price. In this example we will use aluminium - luckily for base metals there are several highly liquid exchanges where futures prices are (typically) 100% correlated with the physical contracts.

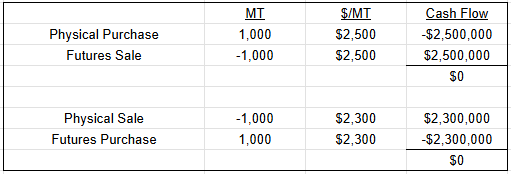

Take a physical purchase of 1,000MT of aluminium. A trader agrees to buy this physical parcel at a price of $2,500/mt. Hedging requires the trader to take execute a futures trade equal in volume but opposite in direction to their physical trade. So in this instance, the hedge for their physical purchase would be to sell 1,000MT of aluminium futures at the same time, and at the same price as they fixed their physical contract. It is important that they execute their hedge at the same time as fixing the price on their physical purchase - if they don't they will be exposed to any fluctuations in the price between fixing their physical and executing their futures hedge.

Let's say that they sell this 1,000MT of physical aluminium two weeks later, and the price on the LME has decreased to $2,300/mt. At the time of fixing the price of their physical sale, they will execute a futures hedge - remembering that a hedge is equal in volume but opposite in direction to the physical trade - their hedge in this instance will be to buy futures at that same price of $2,300/mt.

So, how have those futures trades helped to mitigate the trader's price risk?

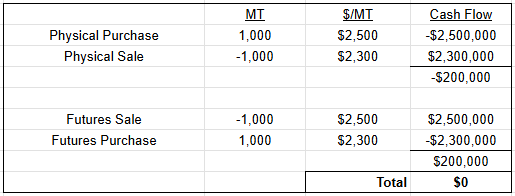

Let's say that the trader had neglected to hedge their purchase or sale. They would simply have bought aluminium at $2,500/mt and sold it two weeks later at $2,300/mt. This would create a loss of $200/mt on the trade. However, since they sold futures at that same price of $2,500/mt, and bought them back two weeks later at $2,300/mt, they have gained $200/mt on their futures trade. They have perfectly offset their price risk on the physical deal.

As you can see, the futures sale offsets the physical purchase at the same price. The same is true for the futures purchase at the same price as the physical sale. To look at these four trades a different way, the trader is losing $200/mt on their physical deal. But they are gaining $200/mt on their futures trade, so the cash flow of the overall four trades is zero.

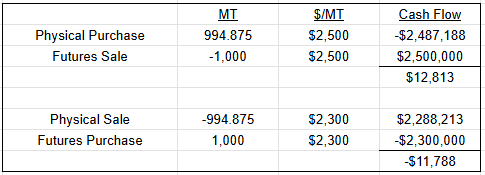

Now, some of you will already be pointing out an obvious problem in hedging base metals. LME lot sizes are fixed - looking at our aluminium example we would be buying or selling futures in exactly 25MT contracts. However, I am yet to come across a physical contract that had final weights of a precise round number, let alone one that was exactly divisible by 25.

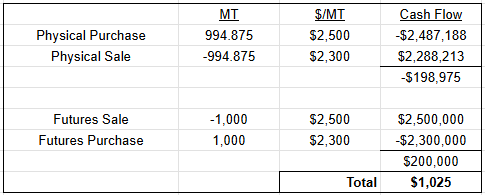

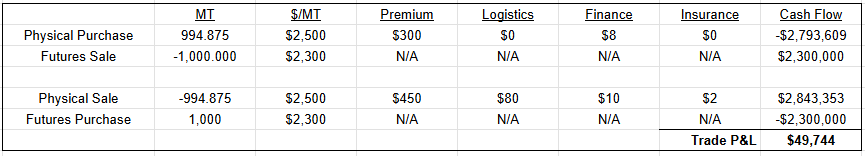

The more likely scenario in this example is one where the final tonnage was within a tolerance of +/- 2% of the agreed 1,000MT on the physical deal. Let's say that final weights came in at 994.875MT. That would slightly change our cash flow totals. While our futures contracts would still be exactly 1,000MT, (the closest we could get to 994.875MT), our physical would no longer be matching. When we say equal in volume, we mean the closes volume it is possible to execute, given the fixed lot sizes that metals trade in.

The slight mismatch between physical tonnage and futures tonnage has caused our cash flows for the trades to move from zero. We are selling slightly more futures than the physical we are buying, and we are buying slightly more futures than we are physically selling.

The overall result of this mis-match is a gain of $1,025 on between the four trades. Because we sold 5.125MT more futures than physical, we have gained 5.125MT more on our futures trade than we lost on our physical trade.

Now this could just as easily have gone the other way. If the price increased between our physical purchase and sale, from $2,500/mt to $2,700/mt, this trade would have lost $1,025 because we would have been losing money on our futures trades, and on 5.125MT more than we gained on our physical.

This slight mismatch is what is known as basis risk. It is part and parcel of trading physical commodities and is one of the risks that needs to be managed on a daily basis by trading companie,s to ensure that these small gains and losses do not turn into impactful gains and losses. See our recent articles on hedge cards for more on this subject: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/hedge-cards-perfectly-hedged-llc-kuecf/?trackingId=JeC5KDMYsAH0rwkRCjbkRQ%3D%3D

You might well be asking, if hedging mitigates the price risk in a physical contract, and a trader can't make any gains from the underlying price, how are they making money? While the answers to that question vary from product to product, and there are many different ways traders can make money, for refined metals the most important factor comes down to the premium. A premium is a value above the exchange price for the metal that is paid by consumers for the metal. It is influenced in a number of ways but in general it reflects the cost of production, finance rates, logistics costs, and the current supply/demand picture for that metal. Importantly premiums can vary throughout the world for the same product, sometimes even varying domestically.

Let's say the aluminium in the above examples is bought at a purchase premium of $300/mt basis FCA Rotterdam. That means that the trader is paying $300/mt on top of the LME price, and they will start incurring costs once the metal has been loaded onto a truck for further delivery. In this example, their final sale is DDP Dusseldorf. For simplicity we will ignore any VAT implications. The trader has negotiated a sales premium of $450/mt from their consumer. This means that if the traders additional costs to move the metal from FCA Rotterdam to DDP Dusseldorf exceed $150/mt, they will take a loss on this trade. If they keep costs below $150/mt, they will make a profit.

Here, the traders costs equal $100/mt from FCA Rotterdam to DDP Dusseldorf, so they are making $50/mt on the trade. It is important to note that profits are initially reported as the gross figures - traders will incur additional costs such as salaries and other overheads that don't typically appear on P&L tables most functions see on a daily basis.